In the 1970s nearly everyone “knew” bats were ugly and dangerous. Virtually all available photos showed frightened bats displaying bared teeth, threatening to bite in self-defense. Photographers simply didn’t know how to photograph such fast-moving, nocturnal animals. So, they’d catch a bat and hold it up for a photo. The bat, fearing being eaten by a giant predator would try to look as vicious and scary as possible. When photos of tiny, snarling bats were blown up to page size, they looked like angry saber-toothed tigers so of course people feared them!

Sharing the real world of bats through photography required getting to know them. But equally important, good bat photographers must help bats overcome their fear of us. Bats are incredibly intelligent and have long memories.

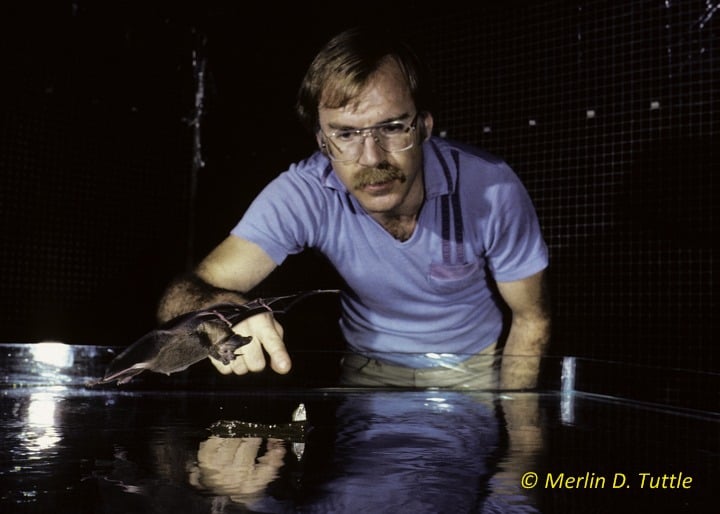

Left: Merlin feeding epauletted bats tamed for his Kenya shoot. They would do almost anything for another piece of banana. Right: Merlin preparing to photograph a newly tamed spectral bat (Vampyrum spectrum) in his studio in Costa Rica. This gentle and intelligent carnivorous species is one of Merlin’s favorites.

Taming and Training Captive Bats

I first learned to train frog-eating bats as part of my research. I had to help them overcome their fear of me so they would respond naturally to recorded frog calls in my research lab. To do that I trained them to come on call to my hand, but to ignore me otherwise.

Later, while training frog-eating bats for a BBC documentary shot in my lab in Panama, I discovered that I also could point to a certain location, remove my hand, and call later, knowing a bat could remember to go where I had pointed, even after I quit pointing. I also trained them not to leave their perches until they heard either my call or the noisy high-speed camera start. In some cases, I additionally trained them to make right or left turns just prior to capturing a frog, to extend the sequence.

My early ability to train bats came from what I had learned in training hawks for falconry as a teenager.

Left: Merlin at age 15, calling his trained Harris’s hawk back from a hunt. Like hawks, he learned that bats could be called for rewards. Photo by Horace Tuttle. Right: Merlin used trained bats and a tabletop set, identical to ponds where bats hunted in the wild for a BBC shoot. He could point to one of several frogs, remove his hand and know a bat would come catch that frog as soon as it heard the camera start.

With frog-eating bats, success began with gentle removal and handling when extricating them from my fine-threaded mist nets. Back at my walk-in flight studio, I’d gently remove a bat from the soft, cloth bag I used for transport. And seated in a chair, I would place it on a cloth bag laid over my thigh. I’d then gently stroke it, and after a couple of minutes, offer it a favored food, typically a small frog. Often, the bat would eat it from my hand. Then I’d very gradually allow it space to escape from beneath my hand and fly to a corner of my enclosure.

Once the bat was free I’d very slowly approach it with another small frog. I wore soft-soled shoes and cotton clothes so I didn’t inadvertently generate potentially scary ultrasounds when I moved. Most bats wouldn’t initially let me get very close before flying away. But I would persist, often moving at barely perceptible speeds. Gradually a bat would get tired and realize that I wasn’t posing a threat. As I got closer and closer it would also realize that I was offering food. Finally, I would be allowed to touch my offering to the bat’s lips, at which point it would usually take it and eat. Thereafter, I’d switch to small bits of easier to obtain minnows. During training, it is best to never offer too much reward at any one time, thereby extending the number of training repetitions.

After a bat had allowed me to approach and hand it food several times, I’d begin softly clucking with my tongue and cheek as I approached. The clucking was done in a manner that generated a wide range of sound frequencies, ensuring bats would be able to hear me. I would repeat this perhaps half a dozen times that first evening, then be sure the bat had eaten sufficiently to last the night before leaving. The entire process normally took about two hours.

Typically, when I arrived on the following evening, holding a reward in my extended hand, the bat would immediately respond to my clucking and fly to my hand to get fed. Though this basic technique has worked well for a wide variety of bats, it is important to recognize that there are as many personalities and IQs among bats as there are among people. Some individuals will be much easier, a few nearly impossible to train. Fruit and nectar-feeding bats often perform well in my studio soon after being acclimated to my presence. However, some hand feeding can speed the process. They normally respond to a mixture of honey and water or fruit juice (provided from a small syringe) or to an appropriate fruit, often a piece of banana. Some insect-eaters are also relatively easy, once they’ve been trained to come on call, rewarded with mealworms. It is best to use small mealworms for small bats.

Don’t count on all taming and/or training being easy. It sometimes requires a great deal of patience and creativity. Training time can be shortened substantially by use of a small enclosure where bats find it difficult to get out of reach of the trainer. I now sometimes train bats to come to my hand on call in less than 30 minutes. Much depends on the trainer’s patience and experience. However, additional time is often required for complex training, such as teaching a bat to remember where I last pointed, then not go there till called, or to turn in a certain direction during its approach. I’m nearly always prepared to spend entire nights, if necessary. In my experience, the most difficult bats have often given in just before dawn.

As in falconry, a bat who has had too much to eat already may not respond well. However, given the high metabolic rates of bats, they’ll usually get hungry enough to work before the night is over. It is always better to wait longer due to over-feeding than to risk a bat’s survival due to under-feeding. One must be especially careful with fruit and nectar-feeding bats, as they can quickly run out of energy and die. When waiting for small fruit and nectar-eating bats to get hungry enough to perform, they should be constantly watched for signs of fatigue.

With experience, one can learn to tell if a bat is suffering from lack of energy. When I enter my studio, I often rub my thumb and index finger together (produces ultrasound) or squeak softly as an alertness test. I expect to see most healthy bats look up and twitch their ears. If one doesn’t, I single it out for special attention, first checking to see if it needs more food. It is best to train new bats one at a time, carefully observing their energy levels.

Pregnant or lactating females should be avoided, both for their own sake and because they are less cooperative. There are no absolute rules, except that roughly handled bats rarely cooperate. In my experience, adult bats have tended to learn faster than young ones. When dealing with Egyptian fruit bats in Kenya, I found that alpha males were by far the easiest to train. These were recognizable by their extra-large testes. I have seldom kept trained bats for more than a week, but it has been my impression that, with more time, they could have been trained to accomplish feats well beyond anything we’ve yet considered, an obviously intriguing but long neglected area for research.

In my early efforts to photograph bats, I assumed that tiny ones, those weighing less than 5 grams (0.18 oz) couldn’t be trained. Thus, when I photographed 4-gram Hardwick’s woolly bats in my studio in Borneo, I only attempted to tame them sufficiently so they wouldn’t fly away when I approached with mealworms. However, after just a single night of hand feeding, one of these bats learned that if he was hungry when I entered, he could fly up and bump me on the nose to get me to feed him. If I didn’t respond, he just kept bumping me till I did. Then he’d land on my hand to get his mealworm—an obvious case of a tiny bat training me! Watch the video here.

Once a bat has overcome fear, it will capture prey, pollinate flowers, or take fruits just an arm’s length in front of one’s camera. Gaining a bat’s trust, much more than expensive equipment, is the key to great bat photos.

Left: Merlin and his wife Paula photographing a Hardwicke’s woolly bat (Kerivoula hardwickii) about to enter a pitcher plant roost in Borneo. This was a six-flash set. Most bats quickly adapt to performing in front of a dim, rheosat-controlled light in Merlin’s studio. Middle: Merlin and helpers setting up his studio in a Taiwan school room. Cords tied to windows and a ceiling panel provided stabilization. Right: Merlin, Toni Hubancheva, and Dani Schmieder (far left) collecting more than 100 pounds of material to build a photo set in Bulgaria. Toni had studied local bat feeding behavior.

Left: Merlin, Toni Hubancheva (far left) and Dani Schmieder building a photo set with material from where photographed bats naturally fed. Right: This greater mouse-eared bat (Myotis myotis) is about to capture a katydid in Merlin’s set. Only one of five bats performed adequately, and it took Merlin and two assistants four nights and hundreds of photos to get this great shot.

Photographing Bats in the Wild

The set should be arranged to have most bats break the beam at an angle, not coming straight at the camera, especially if photographing bats that echolocate through their open mouths. Such bats will appear to be “attacking” if shot straight on.

Bats can be trained in the wild. If one finds a location where they are naturally feeding, especially insect-eaters over a small pond, it is quite feasible to acclimate them to catching insects at a certain pre-planned location where studio lighting has been arranged. I once trained wild fishing bats in Brazil to hunt at a certain location when I called by making clucking sounds. In most attempts to shoot bats capturing natural insect prey, the biggest limitation is finding a sufficiently large number of appropriate insects. I have gotten extremely lucky with a single insect, but often I’ve needed more than 100 to get just one great shot of a capture, whether working in the wild or in my studio. An especially well trained bat can dramatically improve success.

It is also possible to pre-set a camera on a tripod, with a studio-type lighting arrangement, to shoot bats coming to night-blooming flowers or ripe fruits or emerging from a beetle hole in bamboo. This yields especially nice results if extra flashes are used to show the habitat setting.

In Kenya, I trained an epauletted bat in the wild. Males were guarding street lamp territories for their visual courtship displays. However, most could not be approached close enough to permit photos. To solve the problem, I found a theater parking lot where cars entered and exited all evening. Males there were accustomed to frequent disturbance without harm, so could be more closely approached. Nevertheless, perches were obscured by foliage. After mapping one bat’s preferred sites, I used a long pole to make him barely nervous enough to move to an alternate site nearby while I gradually clipped twigs to open a portal through which photos could be shot. On completion, we gently disturbed him at all his alternate courting perches, but never where we planned to shoot. Within an hour, our bat learned that whenever we approached, he could avoid disturbance only by moving to our prepared location. We were careful not to alter his actual courting site.

When shooting bats in natural roosts, such as cut-leaf “tents,” tree buttresses or cave walls, it is important to gradually acclimate them. For roosting bats, I approach slowly, and as quietly as possible, to the point at which the bats begin to show slight signs of nervousness (i.e. increasing ear and body movements). I then stop, perhaps even backing up a couple of steps, and wait for them to calm down.

Next, I take a few photos to acclimate the bats to photo sounds and the light from firing flashes or my headlamp. Finally, I gradually repeat this procedure, advancing just a couple of steps at a time, till I am as close as necessary, often within 10 feet. It’s the only way to obtain calm, inquisitive expressions. And it also avoids potential harm to the bats. Photos of nervous bats are easy to recognize and never of high-quality.

Portrait Photography

Close-up portraits of happy-looking bats can be especially challenging, because it normally necessitates holding them in one’s hand in what for them is an upside-down position. Though I favor adults when training bats for action shots, young ones are often the most cooperative for portraits, not to mention being cutest.

For best results, whenever possible, I work near where the bats are being captured. I mount my camera on a tripod at a height that will be comfortable for me to see the viewfinder at eye-level while seated on my folding stool. I set my focal point to a distance at which the frame size will be most appropriate to the size of bats I intend to photograph. Then I set up three flashes, one to cover the bat’s face and two to ensure cross- and rim-lighting to show detail. I also always use an extra stand with a clamp on top to provide a stable support for my arm while holding bats in front of my camera for photos.

Prior to attempting actual portraits of bats, I normally take one or more test shots of my thumb to double check that all is working properly. I definitely don’t want to lose a bat’s cooperation by taking unnecessary practice shots. When feasible, I like to photograph them as soon as possible after capture while they are still alert. It is especially important to handle them gently, including during capture. I place bats in clean, black bags made of extra soft, synthetic material during transport to avoid accumulation of unsightly lint. When possible, I rely on trusted associates to do the netting or trapping, so I can take pictures while additional bats are being caught.

I use a dim, diffuse light, often hung several feet behind me for illumination. This permits framing and allows me to move the bat back and forth for focusing. Even when a headlamp is necessary, it is best to illuminate the surrounding area, thus reducing squinting. I also dial down my flash power to the minimum needed. This stops movement, such as hand shake, extends battery life, and makes it less likely that bats will close their eyes.

On removal from cloth bags, I’m exceedingly careful to handle bats gently, holding them bare-handed to avoid inadvertently pinching them. A pinched bat will of course never “smile” for a photo! All my movements are slow and deliberate, and I never wear clothing that might generate ultrasound when I move. I sit in a comfortable position and often bribe bats with choice food. Normally, when initially taking portraits, I don’t want anyone else nearby, fearing possible ill-timed sounds that might frighten my subject. However, I also commonly ask an assistant to make varied, soft sounds from over my shoulder to induce a bat to look up out of curiosity.

Use of multiple flashes, arranged to show detailed facial features, often will cause unsightly reflections, especially when photographing bats with shiny black noses or ears. A photographer who wants to show as much diagnostic detail as possible, may have to rely on Photoshop or a similar editing program to remove or tone down such reflections without altering the overall appearance of the bat.

For portraits I use a 100 mm, F 2.8 macro lens on an SLR camera mounted on a tripod with a cable release. The lens is pre-focused to an appropriate frame size, and flashes are arranged on stands to ensure a good ratio of front, back and side lighting. For all my set photography I rely heavily on a fold-out carpenter ruler to measure flash distances to achieve previously tested light ratios that should be adjusted for bats of differing color or facial contours. I always allow greater “fill” lighting for bats with dark colored faces.

All my portrait shooting, as well as virtually all studio shooting is done with both camera and flashes set to manual. Power is dialed down to as little as 1/64 to prevent blur from hand shake or bat movement. F-stops chosen range from 16 to 32, depending largely on varied nose and ear lengths. Focusing lights are dim and diffuse to reduce squinting. Bats used for portraits are normally shot near the site of capture and promptly released. Bats hesitant to open eyes and “smile” may be repeatedly bribed, moved or made curious by unusual sounds made by an assistant over my shoulder. Tiny insect-eating bats are most difficult, often requiring lots of gentle patience.

Standard Equipment

Many modern cameras, flashes and accessories are suitable for bat photography. For most of my career, I have used Canon cameras, lenses, and flashes, and I still use Canon lenses but have switched to a Sony A7 R II and A7 R III mirrorless digital camera body. I highly recommend it for its ultrabright viewing screen, 42 megapixels and focusing aids that are especially useful in portrait and other low-light situations. It also permits use of ultra-high ISO settings, and can be adapted for use with most major brands of lenses, especially Canon.

For all my photography, I keep a small notebook documenting pre-trip tests for each kind of shooting. I additionally maintain a hardcopy photo catalogue for each trip, or series of trips, recording not only names of plants, animals and people shot, but also new flash or set arrangements, or contacts that might be useful in the future.

Sixty-four gigabyte flash cards are downloaded daily to a laptop computer equipped with Lightroom software for photo storage, key wording, and minor editing. Depending on security at a given location, I also backup at least every few days to two independent hard drives, carried in separate containers from my computer during travel.

My two most frequently used lenses are an F2.8 100 mm macro and an F4 24-105 mm zoom. I also occasionally use an F2.8 16-35 mm, an F4-5.6 70-300 mm and an F2.8 300 mm telephoto. I use 1.4X and 2X extenders with the F2.8 300 mm telephoto to create a 400 or more mm lens when needed. “Fast” lenses are especially useful for better viewing and focusing in low light.

Flashes should be capable of power settings down to 1/128 power, in part for stopping speed, though most speed can be stopped at 1/64 power. Flight speed stopping is most difficult for the smallest bats. Depending on the situation, and needs for showing habitat, I use from three to eight flashes, with at least two nearly always positioned to back- and rim-light the bat’s wings. For flash fill with telephoto shots of forest canopy-roosting bats, I use 3X or 5X Better Beamer flash extenders, balancing a single flash with sunlight from above. The extenders focus a flash beam to greatly increase power.

For some flight shots, such as bats emerging from roosts, I use Shutter-Beam (produced by Woods Electronics) with infrared triggering to fire flashes while the camera shutter is held open on its Bulb setting. Several systems are available, but thus far, I know of none that can trigger cameras fast enough to avoid shooting on Bulb. Several electronically skilled photographers have devised special methods of overcoming this problem with specific camera systems, but I still rely on not keeping my shutter open too long prior to a beam strike.

I do not use flight tunnels for flight photos, as they result in too many “straight-on” shots that emphasize bared teeth, aggressive-looking, and generally less interesting photos. They also interfere with needed rim lighting.

All my flashes are powered by eneloop, AA rechargeable batteries. For remote camera and flash control I use PocketWizard Plus II transceivers (only with AA, non-rechargeable alkaline batteries!). I also use various flash light meters and a neutral gray card (for color-correction of portraits). Finally, I typically carry at least three tripods and seven flash stands, each equipped with a ball and socket head.

My walk-in traveling studio is made of heavy-duty mosquito netting, is 10 feet square by 7 feet tall, with a zipper at one corner. A zippered-in black velveteen background covers more than a third of the studio, and 8-inch-wide canvas flaps along the bottom of all sides aid in preventing bat escapes. These are weighted down or taped to the floor. Studio corners are fitted with sleeves for extendable, aluminum poles, and tie loops at corners, midpoints and top-center allow chord attachments tied or stapled to available locations to maintain a steady, upright position. My total traveling weight (equipment and studio) is approximately 350 pounds.

Ethics and Safety

Keep in mind that kind treatment of your subjects will always result in better pictures. Throughout my career, I have consistently attempted to put the needs of bats first, and I hope that users of my advice will do the same. Contrary to overly zealous speculation, there is no evidence of flash lighting harming bats’ eyes any more than it harms ours.

Photos of bats snarling in self-defense can be extremely harmful to public perceptions, as can those of echolocating bats flying directly toward a camera, looking like they’re attacking. Such images can contribute to intolerance and even to mass killing. Please do not share them, nor harm scientific understanding by showing captive bats behaving unnaturally.

Finally, keep in mind that handling or keeping bats without permits is illegal nearly everywhere. Bats are not pets and I advise strongly against touching of any wild animal if not professionally trained and vaccinated. If you are not an informed biologist, but wish to learn about or photograph bats, it’s best to team up with an expert. Most are happy to help. Also, since bats occasionally bite in self-defense, like veterinarians, those who handle unfamiliar animals should be vaccinated against rabies.